Overview

Aztec's global state is a cryptographically authenticated set of data structures that encode the persistent status of the network, updated only when new L2 blocks are sequenced and verified. It is structured as a collection of cryptographic Merkle trees, each serving distinct roles in maintaining privacy, preventing double-spends, synchronizing with L1, and executing public contract logic.

Unlike traditional blockchains that use a single key–value Merkle tree, Aztec maintains multiple authenticated data structures for state. For private state alone, there are at least two main trees: the note hash tree (an append-only Merkle tree for storing encrypted notes) and the nullifier tree (an indexed Merkle tree for spent note tracking). Public state is managed separately in an indexed key–value Public Data Tree, supporting standard membership and non-membership proofs.

Dual-Tree Design for Private State

The private state must be updated without revealing correlations between accesses. If we could link which nullifier relates to which note, privacy would be broken. The standard Merkle key-value paradigm is unsuitable because updates, even if encrypted, would leak timing and structure, making such linkage possible.

To circumvent this, Aztec uses:

- A note tree: an append-only Merkle tree storing note hashes.

- A nullifier tree: an indexed Merkle tree marking spent notes, used to prevent reuse.

This enables safe updates through a replace-via-append strategy:

- Inserting a new note into the data tree.

- Emitting a deterministic nullifier derived from the old note.

Nullifier Computation and Isolation

To prevent cross-contract interference and ensure unlinkability, nullifiers are:

- Isolated by contract (something like

nullifier = hash([contract, base_nullifier], DOMAIN)). - Deterministically derived from note preimage data (ownership secret/randomness).

- Secret-derived: computed using a secret (e.g. the owner's siloed nullifier secret key or note randomness). This prevents linking notes to their nullifiers; even if someone creates a note for another user, they cannot tell when it is spent because they cannot compute the nullifier, despite the computation being deterministic.

Incorrect or non-deterministic nullifier computation risks either revealing identity or enabling double-spend.

Secure State Access

State reads during proving introduce subtle consistency and privacy concerns:

-

Membership in Notes Tree: Users prove inclusion of notes using append-only history. Since the tree never deletes leaves, historical roots can be used.

-

Non-Membership in Nullifier Tree: Must be proved at the head of the chain. A user cannot prove non-membership themselves because the set of nullifiers changes frequently.

Instead, the sequencer performs the non-membership check and inserts the nullifier:

- Transactions include the nullifier.

- The sequencer checks it's not already present, proves non-membership, and inserts it.

- Conflicting nullifiers will cause the transaction to revert.

Read = Write (why reads nullify)

If you were to read a note, how do we ensure you are reading the latest value? The simplest way is to nullify the note after every read and immediately re-create it. This guarantees that any time you read a note (in a constrained environment), you can be sure it is the latest value.

For private, mutable values, you cannot prove you are reading the current value yourself because non-membership in the nullifier tree must be checked at the head of the chain (by the sequencer). To ensure your transaction is valid with respect to the current value, the transaction:

- Emits the nullifier for the previously active note (the sequencer proves non-membership and inserts it), and

- Re-creates the note with the same plaintext and a fresh unique nonce (incremented counter) so it remains available for future reads or writes.

This approach makes reads mutating operations. The main reason for this design is to ensure that the latest value is always available and consistent, not to achieve indistinguishability between reads and writes. As a result, shared notes become mutable: once read and re-emitted, any transactions depending on the original may be invalidated.

Why this pattern:

- It is otherwise hard to know you are using the latest value while proving; membership proofs over append-only trees can be constructed against historical roots.

- Without nullifying-on-read, two transactions can consume the same note concurrently; the first nullifier included wins and the other transaction becomes invalid (race condition).

- Practically, this behaves like optimistic concurrency: the nullifier is the version check, and the re-created note (same plaintext, fresh unique nonce) is the new version.

State Categories and Merkle Tree Types

In Aztec, global state is partitioned across five specialized Merkle trees:

| Tree | Purpose | Type | Proof Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Note Hash Tree | Stores commitments to new private notes | Append-only | Membership |

| Nullifier Tree | Stores spent-note nullifiers, prevents reuse | Indexed | Non-membership |

| Public Data Tree | Key-value store for public contract state | Indexed | Membership + Non-membership |

| L1→L2 Message Tree | Stores inbound messages from L1 | Append-only | Membership (per-message nullifier using message leaf index for replay protection) |

| Archive Tree | Stores historic block headers | Append-only | Membership (used in private proofs) |

Indexed Merkle Trees

For a deeper explanation about Indexed Merkle Trees, we recommend reading this page of Aztec Docs. And if you are really interested in Merkle trees, this might be relevant for your rabbit hole exploration. :::

Used for the nullifier and public data trees, indexed Merkle trees (IMTs) enable efficient non-membership proofs and efficient batch writes:

- Each leaf contains a

(value, nextValue, nextIndex)triple. - Trees behave like a Merkle-linked list, allowing binary search for bounding nodes.

This avoids sparse tree overhead and reduces the cost of non-membership proofs from 256 hashes to log-scaled bounds.

Isolation and Commitment Semantics

Isolation is used extensively across the trees to prevent cross-domain interference. For example:

fn compute_siloed_note_hash(commitment: Commitment, contract: Contract, tx: Tx) -> Hash {

let index = index_of(commitment, tx.commitments);

let nonce = hash([tx.tx_hash, index], NOTE_HASH_NONCE);

let unique = hash([nonce, commitment], UNIQUE_NOTE_HASH);

hash([contract, unique], SILOED_NOTE_HASH)

}

Each note commitment is made unique and siloed per contract to enforce:

- Independence of contract states

- Unique nullifiers per note (prevents nullifier collisions / faerie-gold attacks)

- Ensures every note is unique, allowing multiple notes with the same value (for example, two 10 DAI notes owned by the same user)

Faerie-gold is when two different notes are engineered to share one nullifier. The attacker spends their note first (emitting that nullifier). When the victim later tries to spend, the chain rejects it because the nullifier already exists, leaving the victim with an unspendable note. If an application credited value on receipt before the spend finalized, the attacker could extract value once while stranding the victim. Deriving the nullifier from a unique, siloed note hash prevents constructing two commitments that share a nullifier.

Replay prevention is enforced by the nullifier tree via sequencer-checked non-membership. Note uniqueness exists to avoid different notes sharing the same nullifier, not to provide replay resistance.

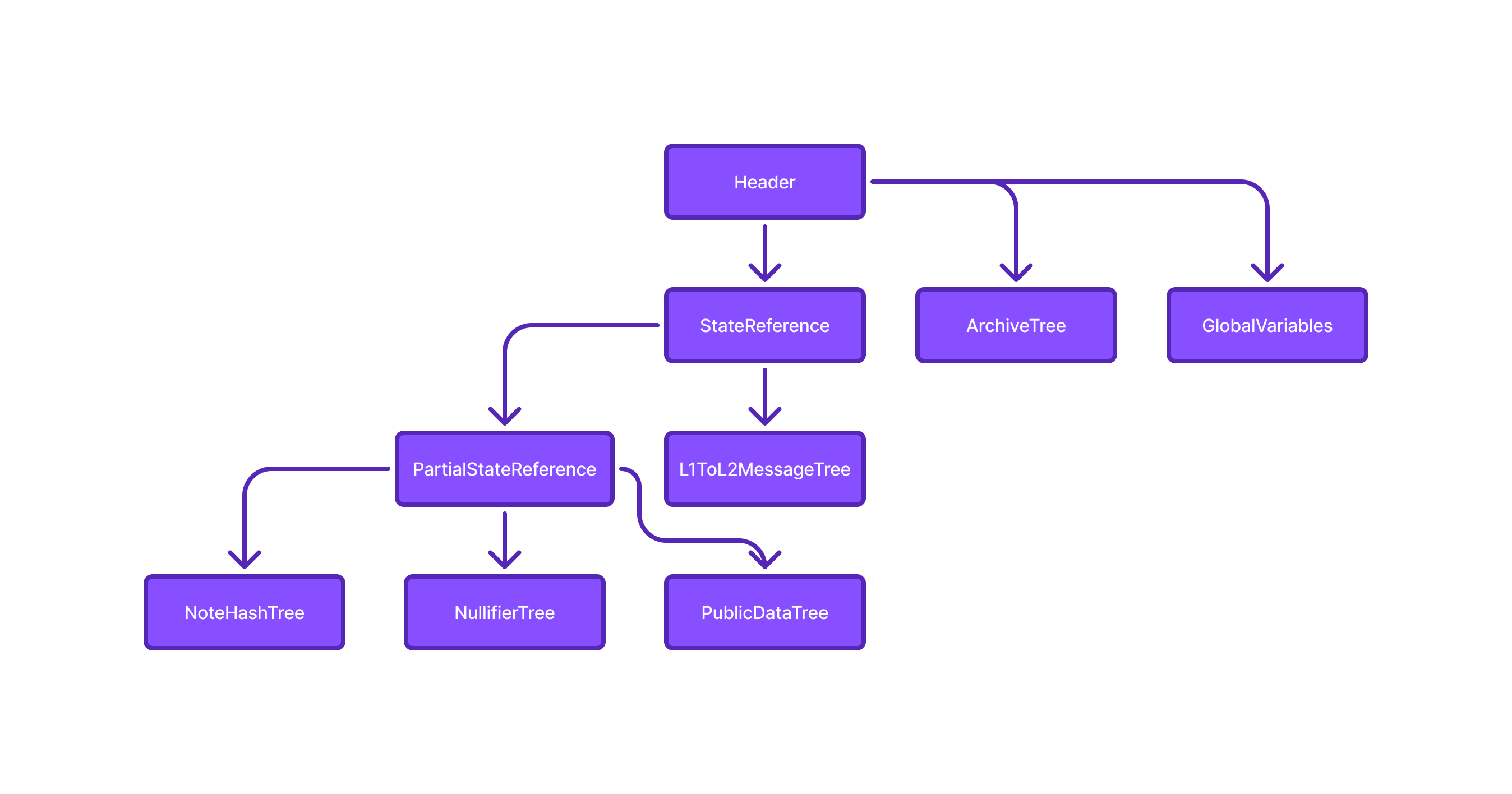

Tree Structure in Header Commitments

State commitments in Aztec block headers include snapshots of each tree. These enable:

- Stateless proving from archived block roots

- Efficient syncing via tree frontiers

Each Snapshot includes the Merkle root and the next available leaf index to enforce append-only semantics.

Wonky Trees and Rollup Composition

Aztec uses unbalanced 'wonky' trees for rollup circuit composition, avoiding padding of empty transactions:

- Rollups are constructed as left-filled binary trees of variable depth.

- This enables efficient aggregation of any number of transactions.

- Output roots are used in L1↔L2 message validation and archive proofs.

See this section in Aztec Protocol Specs for further information.